Good news about the environment is rare these days, but in Tanzania there are signs that local wildlife conservation efforts can effectively protect the natural resources that provide the lion’s share of revenue for the economy. Eco-tourism is Tanzania’s largest economic sector and biggest dollar earner for this developing nation, but wildlife populations have suffered in recent decades from poaching and clashes with people involved in other economic activities such as farming and mining. The good news comes from a new study that found community-based wildlife conservation can quickly result in clear ecological success, with the largest and smallest species being among the winners.

Tanzania’s wildlife resources are among the finest in the world and include the last intact fully functioning savanna wilderness ecosystem in Africa with the largest terrestrial mammal migration and a high density of big game. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, tourism in Tanzania generates around USD $6 billion annually. Tourism brings in 25% of the county’s foreign exchange earnings and regularly surpasses the minerals and energy sectors. Tourism represents 13% of Tanzania’s total GDP, and employs around 700,000 people directly and 1.5 million people indirectly. Tanzania receives more than one million international visitors each year, mostly from Europe and the USA, and the numbers are steadily increasing.

Unfortunately, the benefits of wildlife-based tourism are not shared equally among Tanzanians. There is higher human population density and higher incidence of poverty around protected areas relative to other rural communities, and the rural poor around protected areas depend on bushmeat for the majority of protein in their diets. Additionally, there are complex and non-intuitive interactions among wildlife ecology, the tourism economy, agricultural production, and infrastructure development that complicate the perceived tradeoff between wildlife conservation and human economic development. A World Bank bioeconomic analysis found that economic developments such as higher-intensity tourism, mining, road development, and agriculture which degrade existing wildlife resources would result in an overall loss to the Tanzanian economy. In one scenario, a 20% increase in agricultural profits, and a 15% decline in transport costs (due to infrastructure improvements), that caused a 20% decline in wildlife would result in overall GDP declines of about 7 percent.

The World Bank report suggested the most successful overall national development strategy would be to maximize tourism revenue by increasing quality over quantity, and by strengthening linkages with the local economy by sharing benefits with those who live close to tourist attractions. This strategy lies at the heart of community-based natural resource management. Community-based natural resource management is essentially the transference of resource management and user rights from central government agencies to local communities. It is promoted as a conservation tool and has become the dominant paradigm of natural resource conservation worldwide. Tanzania’s approach to community-based natural resource management is through the establishment of Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) whereby several villages set aside land for wildlife conservation in return for the majority of tourism revenues from these areas. This policy promotes wildlife management at the village level by allowing rural communities and private land holders to manage wildlife on their land for their own benefit, often acting as buffers around national parks. Nineteen WMAs are currently operating, encompassing 7% (6.2 million ha) of Tanzania’s land area, with 19 more WMAs planned.

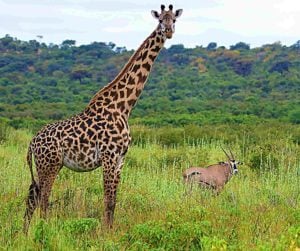

The effectiveness of community-based natural resource management projects for biodiversity protection is not well known because their ecological outcomes are rarely rigorously assessed. In a recent meta-analysis, only 13% of 159 projects included quantification of ecological outcomes. Fortunately for Tanzania, their experiment with Wildlife Management Areas was carefully analyzed in a paper published this week in the Journal of Mammalogy. Scientists from the Wild Nature Institute studying the newly formed Randilen Wildlife Management Area documented significantly higher densities of giraffes and dik-diks, and lower densities of cattle in the WMA relative to an unprotected control site.

Dr. Derek Lee, lead author of the study and Principal Scientist at Wild Nature Institute said, “There have been social and economic critiques of WMAs, but the ecological value or success of WMAs for wildlife conservation had never been quantified. Our data demonstrated that WMA establishment and management had positive ecological outcomes in the form of higher wildlife densities and lower livestock densities. This met our definition of ecological success, and hopefully these results will encourage more community-based conservation efforts.” The positive ecological effects were clearly the result of the WMA because the study found similar wildlife and livestock densities in both the WMA and control sites before WMA establishment, when both were managed by the same authority.

Most community-based natural resource management programs are aimed at promoting conservation while improving people’s standards of living. The Randilen study did not assess changes to local human livelihoods, and that aspect should be formally quantified for WMAs. In the meantime, financial benefits are accruing, and communities have more power and resources with which they can better manage their land and wildlife. Villages are now receiving a direct share of income from wildlife tourism, and the Randilen study has shown that WMAs can provide effective wildlife conservation for areas that are ecologically important. Although most community-based natural resource management programs have only limited success at achieving both conservation and human development goals, the concept appears to be the best opportunity for Tanzania to retain its place as one of the most famous and profitable wildlife tourism destinations while also sustainably developing other economic sectors and alleviating rural poverty.

Citation (open access):